by Steven Zettner, Editor

North Shoal Creek neighborhood begins its neighborhood plan this year. The City of Austin will be looking to add more housing along the neighborhood’s edges in pursuit of Imagine Austin’s ‘Compact and Connected’ and affordability goals. The process is an opportunity to solve some problems, but it is also fraught with long-term risk. Here are five challenges that stakeholders should be considering.

1. Where are the quality transit service areas?

Good land use planning places new housing in areas that will be adequately supported by transit. In fact, the Imagine Austin comprehensive plan enshrines this principle – put new homes and shops close to good transit and walkable destinations, and have less of it away from transit and walkable areas, where people would have to drive. The better the transit, the less that new residents will contribute to congestion.

The problem for North Shoal Creek is that no one knows for sure where or what kind of transit support there will be.

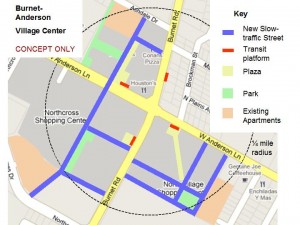

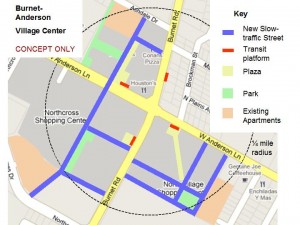

On Burnet Rd, the new rapid bus stations are spaced out every ½ to ¾ miles. The station serving the critical Burnet-Anderson intersection is nearly a quarter mile to the south of Anderson. That makes transfers to east-west buses more challenging. But more important, the south-side station’s location poorly supports properties across Anderson on the North Shoal Creek side. Some of those properties are already zoned to allow higher density VMU. Future residents on the north side will be more likely to drive, and there will be a lot of those residents.

CapMetro planners say the station could be moved in the future. But “could be” is one of those slippery terms that often translates as “probably won’t be.” The current station site was carefully chosen to avoid buses blocking cars at the intersection, and to space the station far enough from the other stations on the line. In any event, without a firm commitment to the station’s long-term location, you can’t make good land use decisions.

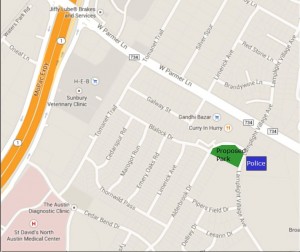

Even more disconcerting is the lack of planning for rapid transit on Anderson Ln. During the ProjectConnect north corridor plan, CapMetro deferred planning for rapid transit on this corridor, and Imagine Austin also assumes no rapid transit. As things stand, Anderson for several decades would only be supported by regular bus service. Yet most of the Anderson corridor is zoned for higher density mixed use, and planners will undoubtedly seek additional places around Anderson to upzone.

At the west end of Anderson, Imagine Austin imagines a neighborhood center scaled similarly to Crestview Station. The assumption is that this site will be supported by a rail station on the Lone Star commuter rail line. But that’s still very much in doubt. Are we going to plan land use in North Shoal Creek for this area, without knowing whether it will get the transit support it needs? Do we have the form based land use types for a rail station – including plazas and strong pedestrian connectivity? The answer is no – we don’t yet know what if any public space provisions will be in the new land development code, because the CodeNext zoning reform hasn’t gotten there yet. The result could be as bad as Crestview Station, or as good as The Triangle or Mueller (both of which required extensive public investment). We just don’t know.

Anderson Ln corridor. Where will the transit be? Where should new housing go?

2. Will there be new side streets?

Several of the properties on Burnet, Anderson and Shoal Creek Blvd already zoned for higher density, or likely to be upzoned, are on 20 acre blocks. For a comparison, a walkable downtown block is just 2 acres. A 2 to 5 acre block makes it MUCH easier for people to walk to nearby stores and transit. It also provides multiple routes for traffic, so that no one route becomes bottlenecked. Small blocks are key to successful walkable, transit-oriented development. Without them, the whole transit-oriented development model falls apart. Congestion will get even worse.

You can’t plan side streets piecemeal. Each time a development occurs, and some side street is proposed, existing residents rightly express alarm that the new street, connecting through to their street, will put an unfair traffic burden on them. Nobody wants more traffic on their street. But if there is to be more traffic, it should be just a little bit more. And the only way to achieve that is to have multiple new slow-traffic side streets that provide multiple efficient routes for both cars and pedestrians within the district. No one street takes the full brunt of traffic, and some of that traffic goes away if people are able to walk, bike, or use transit.

To do that, the City needs to provide a complete plan of future side streets for an entire mixed use district. The plan needs to have teeth to ensure future site plans respect it. Right now, the City doesn’t have a way to do that. And even if it did, it would need to happen on the Allandale and Crestview sides of Anderson as well. Crestview already has a neighborhood plan, and Allandale’s neighborhood association has asked to defer its planning process until more is known about the CodeNext zoning reform.

Concept vision for the Burnet-Anderson intersection, from Sustainable Neighborhoods

3. Will there be pocket parks and transit plazas? Will they contribute to, or hinder, connectivity?

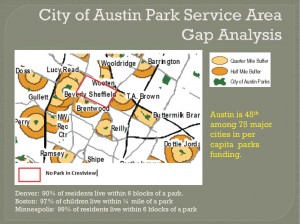

District 7 has the least amount of park space of any area of the city, and what we have is mostly not in locations to support infill development. Parks and Recreation Department (PARD) has a mandate to provide pocket parks within a quarter mile of every residence in the urban core, which happily includes North Shoal Creek (but not North Burnet Gateway or other dense areas just to the north). The problem is that PARD does not treat its park space as a tool for improving connectivity. It often selects park sites that are not in the transit-oriented growth zones, and that will actually draw people out of those zones into lightly populated residential neighborhoods. Park site selection is critical to achieve successful mixed use development. The parks should be in medium-density transition zones. In the case of Burnet at Anderson the northwest corner should have a pocket park in the vicinity of Ashdale, near where existing and future apartments and condos will be located and where lots of residents will benefit. The location of the park should draw pedestrians into the transit district, not out of it.

Unfortunately, PARD often resists getting new parks because it doesn’t have the operational budget to maintain the parks it already has. It got only $4 million in the 2012 bond package for new urban parks (for the entire city, over the next 5-7 years), compared to $30 million for open space on the edge of town to protect water quality. But operational budget is an excuse. PARD should be land-banking strategic urban properties well in advance of when the development will occur. This will promote better planning of the districts, and ensure that the future parks are available when needed. It will ensure the City doesn’t get priced out of park land by its own ‘compact and connected’ policies that drive up land prices.

Transit plazas are another key public space feature. They have the potential to serve as community gathering spaces, drawing people to transit and adjacent stores. Recently the City added a nominal provision for rapid bus transit plazas to the Commercial Design Standards ordinance that governs zoning along streets like Burnet and Anderson. But this provision only requires open space equivalent to a large bedroom, and there needs to be an existing rapid transit station adjacent to the site. So don’t expect transit plazas on Anderson (or meaningful ones on Burnet) based on current rules.

4. Will there be creek trails and natural areas? What will happen with the big drainage culverts that inhibit walkability?

Last year, the City’s Watershed Protection department implemented some exciting changes to the creeks ordinance, providing setbacks even for smaller creeks. The setbacks could enable hike and bike trails, and floodplain areas will be better protected to provide natural areas. This was a great step, and will benefit undeveloped areas in East Austin. Unfortunately, the ordinance exempts most urban areas like on Anderson.

In the urban core, new development that doesn’t exceed the site’s existing impervious cover is exempt from the creek setback requirement. Most sites on Anderson are maxed out for impervious cover.

Also, many features along urban creeks are defined as “highly modified waterways,” meaning that they have been physically altered, reinforced, put underground or in culverts. Those features are also exempt from the ordinance provisions.

Watershed staff acknowledge that urban areas need more analysis. Staff will be attending a Sustainable Neighborhoods meeting on April 9 to look at the Burnet-Anderson and Burnet-North Loop areas as case examples. But there is no guarantee that the ordinance will dramatically improve to support development in the ‘urban core’.

Creek culvert at the Burnet-Anderson intersection. In past ages this was called a moat.

5. Will the new housing preserve existing demographics, or will it exacerbate culture wars?

A study of neighborhoods in eight US cities shows a medium to strong correlation between multi-bedroom dwellings and the percentage of children in the population. To achieve the national average of 24% children in the population, a neighborhood needs a housing mix of 75% homes with at least two bedrooms.

Four-story apartment blocks, like are getting built along Burnet today, are predominantly 1-bedroom units that exclude families. Even 2-bedroom units are harder for many families. Over time, if this is the only housing getting built, and especially if it’s the only housing in the walkable commercial areas, the culture of the neighborhood changes. Retail that serves families moves out; bars concentrate in these areas, causing late night noise and other problems in conflict with the adjacent age-balanced communities.

The key to avoiding such conflicts is to preserve age and income balance in the mixed use areas that reflects the diversity of the existing neighborhoods. Medium-density housing – duplexes, fourplexes, even eight-plexes, are more likely to achieve those goals. Like single-family homes, they are cheaper to build and therefore more affordable. But they come with their own problems. Duplexes are more likely to be rentals, and are at risk of poor maintenance and faster tenant turnover that undermines a strong sense of community. Also, zoning duplexes away from transit adds more cars to area streets.

Many residents fear the challenges from duplexes more than the potential benefits. The City of Austin needs to develop strong tools to address the challenges from these housing types. An example would be much stronger code enforcement. Another would be clearer policies about where it’s appropriate to add this type of housing – in transit service areas but not throughout the neighborhood. Feedback to date from CodeNext staff has been ambiguous on these issues. Meanwhile, real estate advocates are pressing to allow upzoning throughout single family neighborhoods.

Conclusion

North Austin is suburban. Changing parts of it to ‘urban’ means more than just upzoning to allow apartments. And doing it in a way that doesn’t exclude kids, gentrify the neighborhood beyond recognition in the short-term, or leave it vulnerable to decline in the long term, will be even more challenging. This will be an expensive process, and a lot of rules need to change.

North Shoal Creek residents deserve to know what if any policies will be implemented to address these challenges. They should have some compelling assurance on these challenges before considering proposals to upzone — that new housing and destinations will get the infrastructure they need to be sustainable over many decades.

See also:

Austin Needs A Different Way to Prioritize Park Space Gaps

In Search of Urban Parks and Public Green Space

Little Woodrow’s – Big Precedent. The Consequences of Approving a Late Night Destination Bar on Burnet Rd

Sparks Fly As CodeNext Zoning Rewrite Enters Second Year

What Does ‘Age Segregation’ Mean?